Honoring Indigenous History Through Outdoor Learning

Long before Hale’s trails filled with campers’ laughter, this landscape was home to the Massachusett, “the people of the great hills.” Their Algonquian federation included the Powisset, Cowate, Natick, Ponkapoag, Neponset, Pegan, and Wisset, among others, who followed the rhythm of the seasons: fishing and shellfishing along the coast in summer, then moving inland to hunt and gather through the winter months. Evidence of this history remains at Hale today. Carby Street, once known as Old Indian Path, leads to an ancient campsite near Storrow Pond, where archaeologists have discovered felsite tools and arrowheads that were shaped thousands of years ago. These traces remind us that the story of this land reaches far beyond our own.

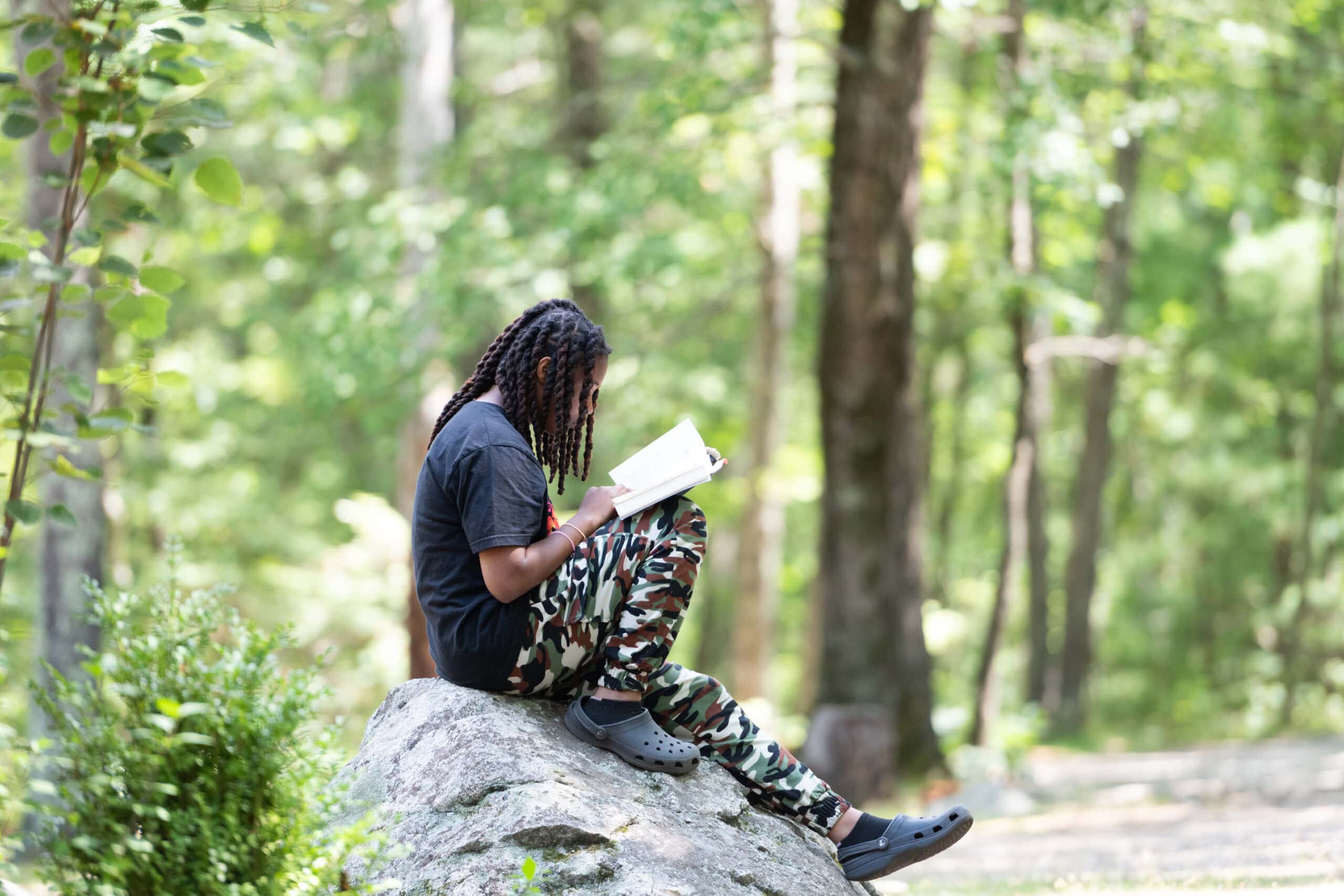

At Hale, that history lives on in the daily rhythm of learning. Through our Hale Outdoor Learning Adventures (HOLA) program, students from across Greater Boston discover that the land itself is a teacher. They brew white pine needle tea, the same kind that Indigenous people once shared with scurvy-stricken settlers. They plant corn, beans, and squash, also known as the “Three Sisters.” These plants, which thrive when grown together, provide a living lesson passed down through generations. They build shelters, carve tools, and explore the same paths once walked by families who called this place home.

“It’s easy to forget who came before us,” says HOLA Director Erik Phelan, “but when we garden, build, and cook here, we’re reminded that the things we do for fun were once vital for survival. It happened right here, on this land.”

That connection is what makes HOLA’s, and Hale’s, approach so impactful. Students don’t just learn history from a book. At Hale, there are opportunities to touch, see, and walk through it. Boston Public Schools librarian and HOLA educator, Iris Santana, describes Hale as “a place where we’re not afraid of difficult conversations, where we talk about the true history of our state and what it means to care for land.”

These conversations grow naturally from curiosity: When a child notices how the oils from their skin can harm certain plants, or says they want “every animal to be safe and happy,” they are already practicing awareness and respect — and learning how to live in relationship with the land, rather than seeing it as something with resources to be extracted or harmed as we use it to our benefit.

While Hale’s programs do not currently involve formal partnerships with Indigenous groups, our educators strive to approach this work with humility and respect, encouraging students to reflect on the history of this land and act in ways that respect it. The goal is to create space for learning, honesty, and wonder, recognizing that every pond, tree, and trail carries the wisdom of those who’ve lived here for so long — wisdom that could serve us well as we look to the future. The children who visit Hale leave with more than outdoor skills; they carry with them a deeper understanding that the land has a story, and that by listening to it, we begin to understand our own.